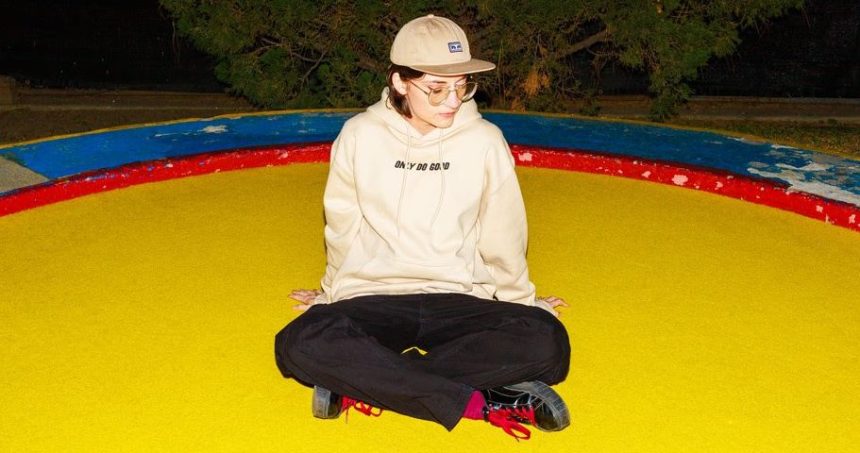

Tongue twisters that mock techno-optimism and cite critical theory don’t usually make for catchy song lyrics. But indie rocker Rosie Tucker’s Utopia Now! finds beauty in the dross of late capitalism. Over 13 songs backed by distorted guitars and blazing drum fills, Tucker’s searing vocals bemoan the inherent dislocation of our modern world while searching for moments of truth and human connection.

Tucker isn’t a new artist — they’ve released a handful of albums and EPs over the last decade — but Utopia Now! represents something of a fresh start. It’s their first full project since getting dropped by their label and firing their management. It also represents a distinctly different artistic approach. While Tucker’s previous work looked inward, Utopia confronts society as a whole. On “Lightbulb,” they describe the feeling of being an artist in the digital economy (“I’m a brain in a jar, I’m a face on a screen”); “Gil Scott Albatross” muses on the modern space race, rueing that “They’re gonna turn the moon into a sweatshop.”

The night before Tucker embarked on a tour, I visited their home studio to speak to them about the inspirations behind their latest album. Although it deals with “big” topics, Tucker stressed that it all comes back to the individual and that the world we have reflects the world we make. “I am trying to reckon with both processing personal resentment,” they told me, “and recognizing my own role in my own misery.”

The opening lyric on Utopia Now! is “The lightbulb is updating, and I sit in the dark.” Why did you want that to be the first thing people heard on this record?

This song was one of the very first I wrote after a long period of writer’s block. And it just sort of naturally ended up synthesizing a lot of the really big themes I was trying to connect. I also wrote it on the piano, which is not normally how I write; I’m not good at it.

It’s arresting because the idea of a lightbulb updating is kind of an absurd statement and also relatable. Like, it’s a failed smart bulb — you’re at the peak of technology and convenience, and you’re sitting in the dark.

Yes, absolutely. A product whose intention is to, like, maximize efficiency has actually failed. I had purchased some colored lightbulbs and they needed an app on my phone to work, and the app needed permission to read all of my text messages. I just felt a way about it, so I didn’t use them.

There’s another line on this song that introduces the tension between art and commerce: “Writing the record / You must want it heard / And return on investment / Is all but assured / Success is a steal / Where the price is obscured.” Did you have any ambivalence making this record?

I loved making it, but I had a great deal of ambivalence participating in a concerted way in the music industry. In the course of creating this record, I was dropped by my label, but that was kind of okay. I also parted ways with one long-term collaborator and my manager. I had just begun to assess the ways that I had kind of sold myself out because I had been functioning under an idea: that if I were to commit myself to trying to be a recording artist in a professional way, it was going to elevate me to a position where I would be able to find my people — people who listen to music the way that I do and relate to art the way that I do. And that was not my experience.

The next track, “All My Exes Live in Vortexes,” kicks off with a striking line too: “I hope no one had to piss in a bottle at work / To get me the thing I ordered on the internet.” And then later you sort of repeat the image, “I know every time you sip from a bottle of piss / And remember me, the memory degrades.” Tell me about writing that lyric.

Yeah, it’s the plastic nature of our minds. I am intrigued by the idea of when you retrieve a memory, you change the memory. And that is so interesting when it comes to personal resentments — how when I resent someone, I am essentially practicing resenting them.

You reuse words in different contexts throughout the album. It’s almost like the way that a memory degrades is the same way that the meaning of a word kind of slips and changes in your brain into something else.

I think that definitely makes me sound like a very coherent wordsmith. I think what is amazing about songs is the forced economy of them, and what that does to language is it kind of really limits the crayons in your box that you have available. And so you figure out how to shade things in such a way where there’s repetition. Because obviously a song lives or dies based on establishing something that can be both interesting and familiar immediately.

But then also you need movement — like at the end of every verse I should be in a different place than I was at the beginning, and every time the chorus happens I should feel a little bit differently about the chorus. So on the one hand there’s so much about songwriting that is so easy once you have your 20 seconds of chords and a melody. The great trick is to pull off something that is coherent.

I’d love to talk about the song title “Paperclip Maximizer.” Where does that phrase come from?

I feel like this is something that I read about on the internet when I was like 13 and the image just has always stuck with me. The paperclip maximizer is a thought experiment about a machine that is so effective at creating paperclips and rearranging atoms that the entire universe gets destroyed. The song, emotionally, is functioning in terms of watching a person who is kind of willing to harness everything in their life to end their own productivity or career.

It’s not a phrase you would typically see in a song. You often pair these academic phrases and words, especially in this track, with some heavy, dark themes, but in a way that is never despairing or flippant. How do you find that balance?

I’m really grateful for that characterization. I had been trying to write songs speaking more to my values for years. It just took some growing up to be able to articulate these things. I needed it to feel totally fresh. Any time that something felt like it could have come from the internet, I would discard it. I had been trying to articulate myself in a specific way in music for a long time, and was just kind of continually characterized as, like, a confessional singer-songwriter. There’s so much value in that, but it wasn’t what I was going for. So I wanted to be explicit and I wanted to be honest and speak from a place of understanding where my own personal stakes were in regards to these wider themes. And then I wanted it to be articulated in a way where it felt like I was talking to someone I respected, because I did not want anyone to feel condescended to.

There’s a lyric in “Unending Bliss” where you say, “I want nothing but unending bliss for my enemies.” Tell me a bit about that line.

I had been trying to reform my own concept of what forgiveness is. I wanted forgiveness to free me and heal me from anger and bitterness that was messing with my well-being. Everyone loves a revenge song. And I think we are in a fairly vindictive moment in the culture at large. But also we are contrasted with, like, conversations around, say, prison abolition, an idea that has become much more mainstream in my lifetime than it was. I just started to think about how the people who I felt really pissed off at are, generally speaking, on my team in the world. Some of the core values, I think, are similar — not similar enough to where I want to ever be in the same room with them, but at some point someone will have to if anything is going to be repaired and changed. Trying to learn how to be more forgiving was part of my own desire to have more agency in my own life, which is not normally how forgiveness is talked about. It’s normally talked about as diminishing us to forgive because we are such good people. We are willing to be diminished. And I just wanted to find something that wasn’t that.

You have a tour coming up. What are you looking forward to about it?

I am just so excited to see people enjoy this record. I went on a tour last November that was just me and an acoustic guitar, and it was very surreal. That song, “Unending Bliss,” had come out, like, two days earlier, and in New York City, people knew the words. And this was a brand-new experience for me. I’ve been writing songs and performing them in clubs for like a decade now. And to suddenly have people who had clearly listened to the music before was quite a trip.