Cats, call your agents. Top creatives are increasingly giving the notoriously tough-to-train pets dramatic roles in live-action projects.

In Steven Zaillian’s acclaimed Netflix limited series Ripley, a Maine Coon dubbed Lucio has been called “a main character.” In Paramount’s upcoming A Quiet Place: Day One, Lupin Nyong’o plays woman struggling to escape an alien invasion with her tuxedo cat Frodo. Last fall, Disney’s The Marvels co-starred a deadly super-powered ginger cat Goose. In Matthew Vaughn’s spy comedy Argylle, which has just started streaming on Apple TV+, Bryce Dallas Howard is on the run from assassins with her Scottish Fold Alfie.

This streak is unusual, and likely unprecedented. Dogs get leading roles in a live-action movies all the time. Cats get leading roles in animated movies all the time. But cats in live action is a whole other ball of yarn. Occasionally a film will put a cat front and center (such as Disney’s 1965 film That Darn Cat and the Coen brothers’ 2013 dramedy Inside Llewyn Davis), but it’s rare. That’s partly because cats have long had a reputation for mucking up shots and testing even the most patient of filmmakers (a notoriety that is perhaps unfair, as we’ll explain later). So cats have largely been treated more like props than characters; relegated to brief appearances for a specific effect — a scare, a laugh, or as a character accessory. When a hero is called to action, their cat gets left behind on the couch. Until recently.

In an early draft of Argylle, Vaughn says his novelist Elly (Howard) likewise left her cat at home before embarking on an adventure with superspy Aidan (Sam Rockwell). “Then I saw a Taylor Swift documentary where she has her cat in a cat-pack and I remember thinking it was a crazy image,” Vaughn recalls. “I thought having the three of them going on an adventure together would be fantastic. I was nervous about it being a cat, because cats aren’t exactly the most trainable animal.” Yet by the time the movie was released, Aflie was front and center in the marketing campaign.

Zaillian was also wary of giving a cat such an important role in his adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley. “I had written the cat into the scripts, and I did it with some trepidation,” says the Oscar winner, who recast the role Lucio twice before finding the majestic and judge-y looking King. “I had this idea that the only witnesses to Tom’s crimes would be animals that couldn’t testify and people who might be uncomfortable testifying. The cat, of course, was the tricky one. Owners would bring cats into the office and think you would want them to do tricks. But what we wanted was a cat that could just be really chill and comfortable with people and cameras.”

And in the upcoming Quiet Place prequel, writer-director Michael Sarnoski (who previously made the Nicholas Cage animal-centric film Pig) likewise gave a cat a hefty role. The movie’s cat wrangler, Jo Vaughan (who also worked on The Marvels), says Day One might be the finest cat performance she’s ever seen in film due to Frodo’s relationship with the story’s human characters combined with some thrilling action sequences.

But what is driving this sudden surge of feline representation?

While there’s no clear and single reason, there are several likely factors at play.

First, cats are arguably in the zeitgeist right now — for whatever reasons govern such things. Vaughn mentioned Swift, who posed on the cover of Time magazine in December as “Person of the Year” with her cat Benjamin Button. And a video game about a cat, Stray, became one of the buzziest titles last year, and is being turned into a feature film.

Another factor could be that Instagram and TikTok have become rather helpful brand ambassadors for the species, with cat videos promoting a wide range of cat expressiveness (one such cat video inspired Vaughn to add a scene into Argylle where Alfie attacks Bryan Cranston). And while cats have a reputation for always looking aloof and impassive, a recent study found they actually have 276 distinct facial expressions (can Vin Diesel say the same?).

“Cats are more expressive than people tend to give them credit for and I learned that massively while looking through the lens when making [Argylle],” Vaughn says. “There are some moments when people say, ‘Well, that shot is so obviously CG and looks fake’ and I’m like, ‘No, no, that was real.’ I was astonished at how emotive a cat is.” CG was used, he adds, when a shot was otherwise impossible. “Like, we couldn’t obviously throw a cat off a building.”

Director Matthew Vaughn behind-the-scenes of “Argylle” with Alfie.

And that’s a third factor: CG animation has become both affordable and convincing enough to portray more naturalistic pets. The technology can clean up a cat’s performance during static scenes, or wholly animate a cat during action scenes (see last year’s Netflix’s drama Fall of the House of Usher, which took cat-from-hell acting in “The Black Cat” episode to a level beyond what was possible in the Pet Sematary films).

“It’s so easy now to do whatever you want with a cat or a dog because it could be done seamlessly with CG and no one would ever know,” Zaillian notes (though in Ripley, the filmmaker got everything he needed from King without CG).

Yet even with digital help, working with cats can be like, well, herding cats. The first cat Vaughn hired was fired because its behavior scared him (“I’m a dog person,” he says). Vaughn instead cast his daughters’ cat Chip, but at one point cat ran off the set which was “in the middle of nowhere” and, as he noted to a reporter during the film’s press tour, “everyone was freaking the fuck out.”

All of which brings us to the fourth and final reason that cats might be getting more screen time: Better training. Professional cat training for films has greatly evolved in recent years, says cat trainer Vaughan (not to be confused with Argylle director Vaughn). Vaughan will typically spend 12-to-14 weeks readying a cat for a film, and always hires at least two very similar looking cats for a role (in case one cat isn’t in the mood to film a scene).

“Training cats is hard,” she says. “But once they’re in the mode of training and working, and once they get the concept, it actually gets easier and easier and easier. I think a lot of [cats’ reputation] possibly comes from people who turn up with cats on a set that aren’t necessarily trained, and so people have slightly bad experiences.”

One common mistake, she says, is when filmmakers put an unprepared cat onto a set and start trying to film almost immediately. On Matt Reeves’ The Batman, there’s a scene when Selina Kyle (Zoë Kravitz) comes home to her apartment and several cats are milling about. Vaughan had the cats spend time on the apartment set for a week before filming. “We got them used to the whole environment, so when it came time to [shoot], they were so comfortable that I literally didn’t even have to be in sight,” she said.

“The biggest thing people get wrong is assuming that cats are not capable of doing [films],” Vaughan added. “Everybody does things with their dog. People don’t do generally do much with their cats, so most people go, ‘My cat would never do that’ — that’s their assumption because they base it on their own experiences. So they presume no cat will.”

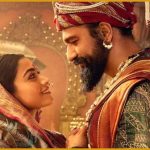

Lupita Nyong’o and Joseph Quinn with Frodo in A Quiet Place: Day One.

Cat Tropes In Film

For decades, cats in movies were mostly used to briefly fulfill a few tropes:

Jump-scare cats: This is in horror films when cats leap out during a tense scene, startling nervous heroes and the audience, right before the killer makes his move. The trope might have originated with 1977’s Alien, where Jonesy brought his orange cat energy to several scenes in Ridley Scott’s horror masterpiece, and Sigourney Weaver became the original badass cat mom, risking her life to rescue Jonesy in the film’s climax (in the sequel, Aliens, writer-director James Cameron sidelined Jonesy with the line, “And you, you little shit-head, you’re staying here”).

Cats as singleton accessory: Pet cats often get briefly shown to convey somebody is living a solitary life (as if living solo with a cat is a bad thing). Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffanys even spelled it out: “I’m like Cat here, a no-name slob. We belong to nobody, and nobody belongs to us.” In reality, cat owners are only 3 percent more likely to be single than dog owners, so this stereotype isn’t really true. The other part of this trope is that lonely cat owners tend to be female while dog owners are male — a stereotype that persists in film today (Would John Wick have worked as well with a cat? Discuss). There is a bit of statistical reality behind this — 64 percent of cat owners are female. But 60 percent of dog owners are also female. So one could say that pet owners overall are more likely to be female, and women are almost equally likely to be a cat owner as a dog owner.

Demonic cats: These tend to be largest cat roles as they’re villains driving the action; an idea that goes back to the 16th century witch panic. Filmmakers also tend to be less skittish about killing off a cat than a dog (“Never kill the dog” is a screenwriting rule cliche, saying nothing about cats).