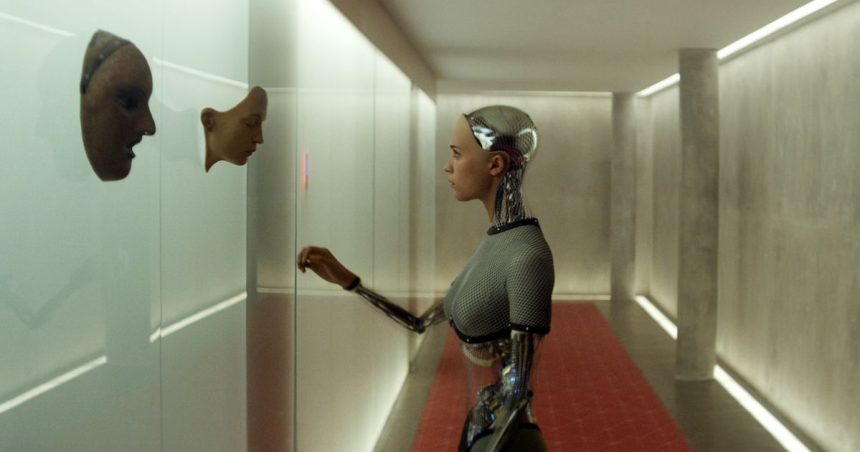

Ex Machina.

Photo: Courtesy Everett Collection

Turns out Alex Garland is not actually retiring from filmmaking. This is good news — love them or hate them, the director’s films are always at least provocative and worth talking about — and the same could be said about his new film out this week, Civil War.

While this will mark only his fourth directing credit, Garland’s filmography is larger than it appears — Civil War will actually be the 11th major film he’s been involved with since his earliest collaborations with Danny Boyle. His best works are defined by their psychological depth and genre ambition, and his plots — whether set on a spaceship staring at the sun or inside of a rapidly evolving ecological anomaly — refract the internal tensions of their protagonists into visual spectacle. So before Garland Soderberghs himself, take the excuse to turn back the clock on his screen output and stream everything he’s ever worked on, from Dredd to Devs.

You may be scratching your head. Didn’t Pete Travis direct this adaptation of the British sci-fi strip Judge Dredd? He did officially, yes, but Garland wrote, produced, and ultimately took Travis’s film away from him and finished it in the editing room — apparently doing so much work that he nearly sought a co-director credit, leading to tension between the two spilling over into the Hollywood press. Dredd star Karl Urban considers the movie Garland’s directorial debut, saying: “A huge part of the success of Dredd is in fact due to Alex Garland, and what a lot of people don’t realize is that Alex Garland actually directed that movie.” That is a solid enough endorsement for us. Dredd, about a broken dystopic future in which fascistic judges patrol and kill at will, totally rips as far as super(anti)hero movies go, and is strikingly better than the Sly Stallone ’90s vehicle, Judge Dredd.

Still one of Oscar Isaac’s hottest, scariest roles, Ex Machina is a surprisingly prescient watch 10 years later, as conversations about artificial intelligence have only intensified. In it a Jack Dorsey–lite techbro CEO challenges one of his underlings to administer the Turing test on a sexy fembot. Driven by references to thought experiments, Ex Machina is one of Garland’s most baldly intellectual films, to the point where the critic Anil Seth wrote this about it in NewScientist upon release: “Emerging from it, I felt lucky to be a neuroscientist. Here is a film that is a better film, because of and not despite its engagement with its intellectual inspiration.” All that, sure, and an open-shirted dancing scene that launched a million memes.

For my money Alex Garland’s best film, Annihilation adapts the Jeff VanderMeer book of the same name: a horrific descent into a transmogrified landscape overtaken by dense foliage, mutated animals, and a kaleidoscopic light called the “Shimmer.” The movie’s soundtrack is a stress-inducing blend of haunting chorals, hypnotic drones, and warm acoustic guitars — a study in weirdness that does nothing to ground the chaotic visuals. Annihilation is sci-fi horror as vibes, probably because Garland only adapted his memory of VanderMeer’s text, and it may make you regret popping an edible. But scenes like its climactic fight and the confrontation with the bear make it worth it.

A swipe at toxic masculinity, Men feels like Garland’s most obvious miss yet. It’s got allusions to pagan myth, anime, and the Garden of Eden, yet, as Vulture’s Angelica Jade Bastién put it, “Despite all the broken bones, the graphic deaths, and the copious amounts of blood, the driving idea behind Men is not bold enough to feel frightening.” It unmistakably carries his style, though, and perhaps the film’s cool critical and commercial reception informed his recent feelings about retirement.

Garland’s latest film Civil War is about a civil war but isn’t really about a civil war. The conflict — which is never meaningfully explained politically — plays out in the background while the film focuses instead on a team of journalists chasing stories as the country explodes around them. Garland, the son of a newsman, has said that he wanted to use the film to make “heroes” of journalists who report from the front lines of conflict. It’s grittier and more realistic than the sci-fi works Garland is known for, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

One of the most distinctive zombie movies of the last quarter-century, 28 Days Later breathed new life into the horror genre thanks to director Danny Boyle’s use of gritty, early-digital cinematography and propulsive use of Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s “East Hastings” in the score by John Murphy. (Also notable: The zombies are fast, not slow!) But it wouldn’t exist without Garland’s story, which was informed by genre classics like Night of the Living Dead and Resident Evil.

A crew of eight whiz through space on a mission to rekindle the sun by bombing it. What could go wrong? Garland’s script tests their camaraderie as relations rapidly deteriorate in the face of bright, glowing doom. Sunshine is informed by Solaris, the heat death of the universe, and Bill Bryson’s A Short History of Nearly Everything — inspiration that Garland and director Boyle synthesized into one of the boldest, claustrophobic sci-fi films of the ‘00s. Watching it today, it’s also a blast to see actors like Cillian Murphy, Rose Byrne, Chris Evans, and Michelle Yeoh play off each other.

Topping the instantaneous word-of-mouth hit 28 Days was always going to be a tricky proposition, but the sequel lives up to the horrific spirit of the original. While Garland primarily contributed to it through notes (he and Boyle served as executive producers, while others wrote and directed), and in the past he’s described it as “not subversive” (without really explaining what he meant by that), it’s still a linchpin in his canon as a filmmaker. He’s acknowledged that it made plenty of money, and since reportedly getting an idea for a third film about a decade ago, he’s been more protective of the franchise. As of the latest reports, he’ll write 28 Years Later and Boyle will direct, as they did the first one.

Novelist Kazuo Ishiguro’s weepy cloning love-triangle story turned out to be apt source material for his friend Garland to adapt. The film directed by music video god Mark Romanek is characteristically stylish — filmed on a 35mm Kodak film stock that gives its sci-fi a naturalistic, dreamily vintage feel. We won’t spoil the story’s plot except to say that there are clones and that the movie works as a meditation on humanity, art, and love.

The last vestige of Leonardo DiCaprio’s awkward years after becoming Hollywood’s biggest young star in Titanic’s wake, but before working with Steven Spielberg or Martin Scorsese, The Beach made for a better book than it did a movie. (Leo earned himself a Razzie nom.) It just doesn’t capture the tension of the novel’s characters or the darkness that its beachfront utopia in Thailand represents. It did however team Garland with director Danny Boyle and producer Andrew Macdonald, who became career-long collaborations — not a total wash.

Based on another Garland novel set in Southeast Asia, where he spent time traveling, The Tesseract is like an action-thriller riff on Crash: What if the disconnected lives of a drug runner, an assassin, a psychologist, and a bellhop all collide through a complicated series of events? Directed by Oxide Pang and adapted for the screen by Pang and Patrick Neate, The Tesseract, manages to eke out some of Garland’s early ideas about determinism, fate, and human psychology, but the filmmakers’ efforts didn’t convince critics. Today it’s a hard-to-find artifact of early ‘00s film.

Garland’s only TV show grew out of a skepticism of technology and free will. Like Ex Machina before it, it’s a parable pushing back against how much self-styled tech companies dominate our lives, but it stretches its reveals out across eight episodes and can sometimes feel “frustratingly opaque,” as critic Jen Chaney put it. It is Garland at his most Garlanded, and love him or hate him, that may be more than enough.