On the surface, Guantánamo Bay may seem like an unlikely target for Sarah Koenig, Julie Snyder, and the Serial team, still principally remembered for spectacle generated from the first season’s real-time true-crime reporting on the case of Adnan Syed. But as Koenig notes in the introduction of season four, this is a story they have been trying to pull together for almost as long as the podcast has been around. “Even as Guantánamo faded as a topic of national discussion, we kept thinking about it,” she narrates. “We even tried writing a TV show about it, a fictionalized version of Guantánamo.” The latest season, then, is an effort coming full circle.

If there’s a clearer symbol for America’s “War on Terror” boondoggle, it’s hard to think of one. Since Guantánamo opened for extrajudicial business in 2002, almost 800 individuals have been held in what functions as the U.S. government’s prison for suspected terrorists—all Muslim, most from the Middle East — but vanishingly few matter in the U.S.’s counterterrorism campaign. Despite flimsy promises from Presidents Bush, Obama, and Biden to shut the place down, the lights are still on. The camp, with its dozens of remaining detainees, continues limping along, a piece of machinery left to gather dust in the country’s basement. The U.S. pulled out of Afghanistan, but the forever war persists.

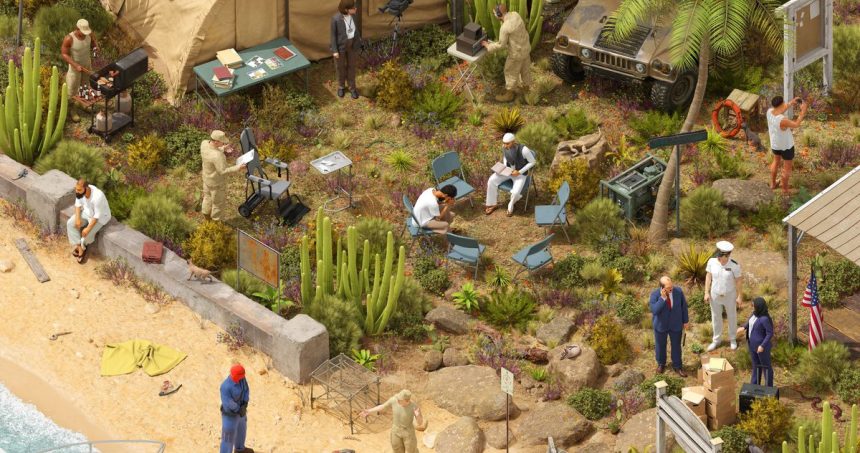

It has been six years since the podcast’s last release and almost a full decade since Serial turned into a household name. Now, Koenig and co-host Dana Chivvis ask a question less muck-raking than anthropological: What exactly was Guantánamo like on the inside? Eschewing the serialized structure that gave the show its name, the season is built on short stories drawing direct testimony from a gallery of individuals — detainees, guards, wardens, intelligence personnel, translators — who knew the place firsthand. It shares the same construct as Serial’s third season, which documented the banal goings-on in a Cleveland courthouse. The purpose isn’t to solve a mystery but to piece together the sense experience of a place.

This approach spotlights the team’s gift for provocative detail, which hits you in episode one when Koenig and Chivvis revisit recordings from a guided tour of Guantánamo they took years ago. They hook you with the surreal observation that there are three gift shops at the facility; you might stumble upon Guantánamo x Disneyswag. The moment transitions into a pitch-black admission that the longer they spent in the camp, the more their initial halting discomfort about the shops melted away. They bought merch.

That permeable line between perverse surreality and inevitable normality runs through the season. When a former camp guard relates his experiences, you begin to understand how Guantánamo is a workplace like any other, even if it involves violations of international law. You get the sense of human beings being inexorably shaped by the roles they’re plugged into, their moral compasses shifting over time. Many episodes circle around a scandal in Guantánamo’s history to draw out the brutally Kafkaesque nature of life on the inside. “Ahmad the Iguana Feeder” and “The Honeymooners” recount the story of Ahmad Al-Halabi, an American airman brought in to serve as a translator only to get caught up in a punishing swirl of government racism and bureaucracy. “The Big Chicken” and “Asymmetry” revolve around a warden who oversaw the facility during one of its most ruthless and disputed periods. Across these stories, the individuals in charge try to make meaning out of their power. Meanwhile, former detainees attempt to process the horrors, physical and psychological, they endured. Although some of these stories are not particularly new, Serial’s primary interest is to thread them all together within a feeling: This is what it was like, and this is what it’s still like.

What is Serial supposed to be, anyway? You’ll often hear the critique that the show never successfully replicated the energy of that first season, even as Serial Productions, the studio spun out from This American Life to house Koenig and Snyder’s future projects, continues to be a reliable publisher of popular podcasts, including S-Town and, more recently, The Retrievals. But spectacle was never Serial’s intent. This should’ve been readily apparent when, in season two, Koenig and journalist-screenwriter Mark Boal explored the case of Bowe Bergdahl, the U.S. Army sergeant who abandoned his post in Afghanistan and was captured by the Taliban. At the time, the second installment inspired feverish anticipation. But when it arrived, its insistence on reframing the focus away from the specific mystery (“What happened to Bergdahl?”) toward a larger idea (“What does it mean for us to keep sending young people to war?”) felt, for many listeners, like a dramatic deflation. The third season, set in the Cleveland courthouse, pushed further in this direction, not only throwing aside the notion of needing a catalyzing mystery but also challenging the importance of Serial itself. “People have asked me and people I work with the question, What does this case tell us about the criminal-justice system?” narrates Koenig, referring to Syed’s story. “Fair question.”

Pointing out the remarkable nature of oft-overlooked systems has turned out to be Serial’s underlying project. In the scope of who gets incarcerated in the U.S., Syed’s excruciatingly drawn-out case isn’t all that notable. Bergdahl’s might be extraordinary, but the blindly accepted notion we send kids to war isn’t. What happens in a courthouse is banal, even if it destroys lives. Guantánamo has been running for more than two decades, and now, buried beneath other political horrors, it has become an unremarkable part of the American story. Serial’s focus on it is perfectly aligned with what the team has always done: Dust off the machinery of power and render its parts visible.