Hark, fair maids, lairds, and theys of the Vulture kingdom! Hath thou caught up on one of the absolute best series on TV so far this year, the three-part HBO docuseries Ren Faire? If not, it’s a must-watch. If so, then you’re probably full of outstanding questions about the state of things at the Texas Renaissance Festival, still overseen by “King George” Coulam. The show is Succession for LARPers, an insightful look at an aging narcissist and the subjects in his orbit, namely the pretenders to the throne: the passionate thespian and general manager, Jeff Baldwin (and his wife, Brandi); fellow but much more no-nonsense GM Darla Smith; and Red Bull–swigging kettle-corn mogul Louie Migliaccio. All of this is executed in fantastical, intimate style by filmmaker Lance Oppenheim.

Working with the Safdies’ production company Elara Pictures, Oppenheim has already released two of the best documentaries of the year so far, between this and Spermworld, a feature on FX and Hulu about under-the-table serial-sperm donors. Both projects follow participants in kind of strange, fundamentally American subcultures and illustrate their psychological hang-ups and hopes in ways that render them scarily relatable to the rest of us. But only one of these projects made me cry with a song from Shrek the Musical. Below, a conversation with Oppenheim, a documentarian for a new age, for the true freaks and dreamers.

Is the cast all watching? What do they think of it?

I’m in constant contact with Jeff, Brandi, Darla, Louie, and to some degree George, too. Everyone has seen it. Jeff told me, “Thank you for making something so wonderful out of something so horrible.” I relate to that. It was a really transformational, amazing experience, but it was also very painful to be there and just to bear witness to it all.

Jeff is clearly someone who processes his own life through fantasy and art. Did you feel a kinship with him, as a creative?

Yeah, 100 percent. I remember the first time I ever met Jeff, we talked for about 30 minutes, and he allowed us to start filming with him 30 minutes afterwards. I think it was our second day of being at the faire in 2021, and that led to the scene that’s in the first episode where he’s saying, “Here’s me as Shrek,” and talking about how his father died during the middle of rehearsal for this play Daddy’s Dyin’: Who’s Got the Will? So the emotions of the play, everything he experienced, were real.

I feel like that’s such an apt way to describe the experience of his performance in this whole show, because like any documentary subject, when a camera’s right in front of their face, they’re going to be performative to a certain degree. But for him, it was this weird mixture of therapy and theatricality. In a way, it’s a true method performance. I wish there was an Academy Award for documentary-subject performances, because I feel like he should be honored and celebrated for the vulnerability and the trust he had with us, and also for his willingness to collaborate with me and turning his real life into, hopefully, cinema.

How do you gain access and trust from your doc subjects? I imagine in these subcultures, they might be wary of gawking outsiders.

I think every story and every world has its own set of rules and logic that everyone adheres to. And certainly with the Texas Renaissance Festival, it was pretty clear when I first got down there with David Gauvey Herbert and Abigail Rowe, the journalists who brought the story to me, that there was a culture of fear. A lot of people did not want to speak poorly of, or speak out against, George. What it actually reminded me of was the Twilight Zone episode “It’s a Good Life,” where everyone was sweating as they praised this person. When I finally met George, I realized he indicts himself by behaving the way he behaves. I thought it was probably best to just let him be himself, uncensored. No one needs to say anything negative about him.

The pitch for the people involved, when I first met them, was always “I’m interested in the past, the present, and the future of the festival — how it came to be, how George created this thing, what’s actually happening now, what he’s doing to get the future intact, and then in the future, who’s going to run the place?” As time went on, the question sort of shifted. It started to become less about who will be the next king and more about the story of a man of advanced age who is clinging desperately onto the power he has in the system, the fiefdom, that he’s created. It’s a portrait of an American empire in retrograde, in miniature. It feels like a version of the reality we live in. There’s this cycle that George inflicts upon other people, and I think there are a lot of different Georges in our society that are inflicting that kind of pain on a lot of other people.

George is someone who clearly needs to be in control of any situation he’s in. So as a director, was he hard to work with?

George is a complicated person. But I really am grateful that he gave us his time and access, and the fact that he was so extremely vulnerable. Because he controls so many people in his society, I think he’s very lonely, and he was looking for an outlet — maybe not to make friends, because I don’t think he’d consider me a friend, and I wouldn’t consider him one either. But I listened to him. He had a captive audience. When we were filming with him, it was much more of a dance than I’ve ever really had with any documentary subject before. If I tried to shoot something that felt very controlled or composed, he would quickly run out of patience. We’d be filming and I’d say, “George, if possible, just try not to acknowledge us. Try to go about your day as you normally would, with the people that you’re normally with.” But he would resist that, and look at me to say things.

At first, I thought maybe he just doesn’t understand, and maybe I need to tell him again. But when we were at a nail salon with him, as featured in the third episode, you don’t see this interaction, but I was telling him again, “Hey George, maybe just don’t talk to us.” Then I went back to watch the monitor, and the nail technician said something to me, and he corrected her and said, “Don’t look at the camera. Look at me. Just pretend they’re not there.” At that point I realized George is extremely savvy. He’s a trickster. He loves to play with people. As documentarians with cameras, there’s a lot of control we wield. We had to find ways to minimize the feeling of that and ultimately be flexible and loose when we were with him. You feel it in the photography. The camera is handheld and a lot more mobile with him.

How about filming his dates at Olive Garden?

I think he must go on at least three a week. I thought filming it could reveal a different dimension of his psychology. Here he is, with someone who he’s controlling in a way, because he’s paying for lunch, and he’s lewd with them. But there was something very interesting that happened towards the end of the conversation, which is him opening up to them a little bit. The date asks him, “Won’t you miss being king?” And he says, “Shit, no! I hope not.” And that “I hope not” was the first time I’ve ever heard him say anything other than “Yes” or “I’m ready to go, I don’t want to do this anymore.” And right after that moment, he so quickly turned on her, and turned on the whole experience. I think that vulnerability that he showed just for that one moment made him retreat back to this very punitive place where he feels much more comfortable. Even at the end of the other date that doesn’t go according to plan because, uh, the woman doesn’t have natural breasts, he takes it out on everyone. He’s so upset about that experience that he can’t control his impulses and rage.

George is very powerful, but he’s also definitely elderly and somewhat vulnerable. How do you approach filming a subject like that with sensitivity?

I treat them as I treat everyone in general. It’s an invitation to a process. If someone doesn’t want to go there with me, and they’re not interested in that line of inquiry, we usually just won’t make the film together.

But now I can show them my earlier work and say, “Hopefully I can merge the filmmaking process and drench it in your subjectivity, and your emotions, and your inner life, and your hopes and your dreams and your desires, and the obstacles that are blocking them. And if I can do my job correctly, then hopefully it will be an unbelievably immersive experience — not just for yourself, but for an audience, to open up pathways of understanding.”

What was the process of filming the more fantastical, staged scenes with Jeff?

I think there’s something interesting about how Jeff’s performance, specifically, changes a lot over the course of the series. In the first episode, it’s maybe more coming from a fear of George and this instinct to praise him. In the second episode, he’s defensive and trying to muster the courage to actually say how he feels to him. And by the third, it’s a feeling of betrayal and ultimately resignation to a life that he’s destined to lead, which is to be a part of this merry-go-round. There are fantastical moments because Jeff and I were so aligned and on the same page from the moment we met each other. I even share the same birthday as Jeff. We really clicked on exactly what we thought this could be. We talked a lot about the way he sees his life as this Shakespearean story. He’s constantly talking about King Lear; he references The Madness of King George. So I wanted to do something that could speak to the theatrical, operatic way that he views his situation.

The same went for Louie, whose references were more contemporary. I remember when I first met him, he said, “It’s a real-life Game of Thrones out here. People are stabbing each other in the back all the time.” And I think Darla was someone who said, “Whatever you do, please don’t make this Tiger King.” Tiger King was a very sensational show. I’m not trying to over-sensationalize the drama here, but I want to create this true experience that isn’t just objective documentary. It’s something different. It’s almost like simulating the experience of going to a renaissance festival.

There’s a scene in the second episode where a dragon speaks to Jeff. That was a moment where I knew Jeff was in a really dark place. I had done an interview with him, and he basically told me his feelings, and I knew he was hoping to speak to George. I thought, Why don’t we do something that can express that feeling in cinematic terms? As I was describing this to him, this guy in the dragon costume came into his office to ask him a few questions about participating in the faire the following year, and I was like, “Why don’t we just shoot something here? This is great!” And then in post-production, the dragon’s voice actually belongs to Jeffrey’s brother Greg Baldwin, who’s a voice actor who does voices on Samurai Jack.

Just because there’s this collaborative effort between myself, my crew, and the participants in the film, it doesn’t make it any less truthful. The pain was real, the emotions were real, but the fantasy is also real. It’s real to every person that lives there. That’s what keeps them there.

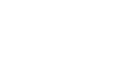

The dragon.

Photo: HBO

Why’s Nathan Fielder in the “special thanks” section of the credits?

Oh, Nathan’s a good friend of mine, and he was very gracious, too, as was his editor, Adam Locke-Norton. They both watched many cuts of this project as we were figuring it out in the edit. He had basically told me that a lot of people would reject the flair of this thing if they didn’t understand that it was part of the construction — that the only way to experience the emotional moments of this is to enter the looking glass and come out the other side. So he was like, “You gotta find a way to address this. Do you do guys do press notes?” And I was like, “I don’t think HBO does press notes.” And he was like, “Oh, okay. I thought they did them for my show.” And I was like, “I don’t think that’s … Let me inquire.”

Then my editor Max Allman came up with the idea to call it a “docu-fantasia.” I kept pitching it to HBO, and eventually they let me put it in the South by Southwest description. It helps position that these moments of artistic license are truthful, and explain that these people’s performances in those creative, expressive moments is documentary, unto itself. And because he suggested doing something like that, he deserves a special thanks.

Are there any other elements of the faire that you wished could make it into the final version that didn’t?

Yes is the short answer. Probably 10 percent of what we filmed is in this project, and a lot of that was the lives of the community at large, the people that live in the community for artisans and vendors that George helped build a long time ago. But I think the more time I and my editors Max Allman and Nicholas Nazmi sat with it, the more we knew it had to be about the question of who would be the next king. And ultimately, the answer being George felt very apt. All documentary editors are writers in a way. They help assimilate footage into something that’s consumable and meaningful. They have a writing credit on this, because they really taught me what the story was.

Every time we were too far away from the sun of this solar system, George, something felt like it was broken a little bit. And because we only had three episodes, I knew that as a saga, it had to stay close to not just George, but also Jeff and the emotional experience he goes through, because that’s what influenced my artistic approach more than anything. Even the third episode, after he gets fired, we changed the way we shot a lot of it. I changed the lenses to something a bit more digital and colder, and the color temperature changes, and there’s less Steadicam. Ultimately, it was a long, several-year process of an edit, and the edit would go on as we were shooting, but I’m happy with the edit in the end.

Speaking of reality TV, I saw you cited Vanderpump Rules as an influence, right alongside documentarians like Frederick Wiseman.

Look, Bravo has changed the game for not just reality TV, but really for cinema in a way. A lot of filmmakers watch reality TV just as much as they watch Stanley Kubrick movies. I love Bar Rescue and Restaurant Impossible and Kitchen Nightmares, even To Catch a Predator. There are these hyperreal moments that are just so raw and painful to watch, and then it cuts back into this commercial pop aesthetic. People engage with them in a way that’s similar to how they’d engage with a Hollywood movie.

No one’s really questioning the sense of reality or manipulation when you watch a reality-TV show. I would never call what I do “reality TV,” because there’s no script and there’s no story producers, and it’s not like I’m forcing things to happen. I let reality happen around me, and then I try to find ways to express it in really cinematic terms. But if I can take very commercial ideas or worlds or settings and find something really deep within them, hopefully as people watch them, they stop asking about what’s real and what isn’t and they just are able to emotionally engage with the experience of it. I think that’s just like they would with the reality-TV show. That would be great, but hey, maybe I just need to work with Jon Taffer or something.

Reality TV governs our existence. We had a reality-TV president of the United States, and who knows if it happens again? I don’t appreciate when people bad-mouth it, because there’s a lot to learn from it. And yeah, Frederick Wiseman is truly brilliant. I’m trying to do something between these two things.

How much more B-roll do you have of Louie vaping and pounding Red Bulls?

Even when I was showing Ren Faire to him, Louie was crushing a Bang energy drink. There’s a moment where you see a sign in his room that he’s sober. But he has this dream of buying the festival, and what it takes to get there means he does not sleep a lot. He just lives, eats, consumes, breathes festival. He doesn’t just attempt to buy it. As you see in the first episode, he’s a millionaire, but he’s also a man of the people. He’s in the kettle-corn booth sweating his ass off as he’s singing Lady Gaga.

In the last scene with him, there’s a moment where everything slows down, and he’s smiling at George while George consistently gets his name wrong, it’s about the cost of all of this. And I think for Louie, it’s a very physical cost. By the end of the show, it’s almost like everyone has aged dramatically. Everyone looks like a different version of themselves. A lot of it is the latent stress of just existing there, and the psychic costs of being a part of the kingdom.